At the close of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1789, legend has it that a woman called out to Benjamin Franklin to ask what kind of government the delegates had created. Franklin responded “…a republic, madam. If you can keep it.”

A republic?

Shouldn’t Franklin have said “a democracy”?

Isn’t that what we have in the United States?

Most people today would say “yes.”

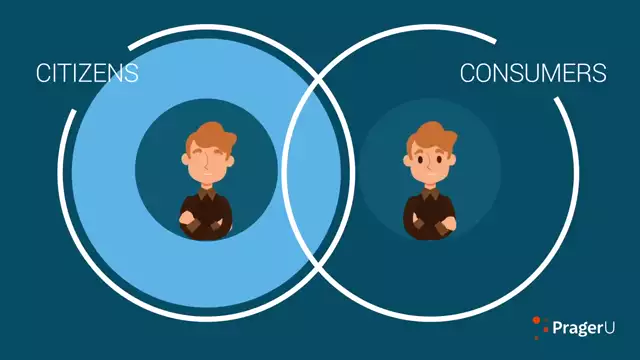

After all, if our country isn’t a democracy, what is it? It’s not a dictatorship, the rule of one man. Or an oligarchy, rule by a small group. In America the people are in charge. That’s literally what democracy means in the original Greek—demos kratos—the people (demos) rule (kratos).

But let’s pause for a moment and consider more deeply what the word means in practice and why the delegates in Philadelphia rejected it.

That’s right—rejected it.

Our government was established by a national charter—the Constitution of the United States. We are governed by the institutions, and according to the rules and principles, created and adopted when our forebears ratified that document, making it “the Supreme Law of the land.”

Are those institutions properly speaking democratic?

The men who bequeathed our form of government to us—those we call our founding fathers—didn’t see it that way.

They understood the institutions established by the Constitution to be republic.

In fact, though the founders believed in “government of the people, by the people, for the people” as Abraham Lincoln put it in the Gettysburg Address, they did not believe in pure or unrestricted democracy. They feared that democracy, strictly speaking, contained within it the impulse to mob rule—the stifling of civil liberty, the trampling by majorities of the rights of minorities.

To put it more bluntly, pure democracy frightened them.

So, while they built into the Constitution significant democratic elements, they also built in non-democratic features to protect liberty and prevent tyranny. It wasn’t simply that they favored representative government over direct democracy, though they did; it’s that they rejected the idea that “the majority wins” was by definition the just outcome.

Indeed, in what is perhaps the most famous of the eighty-five Federalist Papers—Federalist 10—James Madison, precisely in distinguishing a democracy, which he did not favor, from a republic, which he did, noted that a crucial advantage of republicanism is “to refine…the public views by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interests of the country…”

And, so, we have representative government, and more than that, we have a bicameral (that is, two-tiered) legislature—a Congress with a highly democratic House of Representatives and a not-very-democratic Senate.

Therefore, California, with its massive population, has fifty-two representatives in the House. Wyoming has one.

Yet Wyoming has two Senators—the same number as California and every other state.

A pure democrat would say, “that’s unfair!” Each Wyoming resident has far more power than every Californian.

But a republican would say, well, we aren’t and shouldn’t be a pure democracy. If we were large population states like California would overwhelm the needs and interests of small population states like Wyoming.

That’s why we’re called the United States of America. Each state has its own separate identity; holds its own separate elections. Just as we don’t want one person or small group of people to dominate our government, we don’t one state or a few states to dominate our government.

A republic is a way of diffusing power—and a brilliant one at that.

We see something similar in the Constitution’s procedures for choosing a president. An obvious possibility would have been by a national popular vote. The founders wisely decided against this option. Rather, they created an electoral college to protect the interests of the less populous states. Even today, their decision makes sense. As my Princeton colleague Professor Allen Guelzo observes, “a direct, national popular vote would incentivize campaigns to focus almost exclusively on densely populated urban areas.” The electoral college system incentivizes candidates to court voters more broadly—making presidential elections more fully national.

So, if we understand the system of government our founders bequeathed to us, we will see why they preferred to describe it as a republic rather than a democracy. Of course, it has strong democratic elements, but America was not created to be a pure democracy for very good reasons.

Those reasons remain as valid today as they were in 1789.

We should not go along with those who today are demanding constitutional changes simply because this or that institution or procedure established by the Constitution—say the Senate or the electoral college—is not “democratic.”

“More democratic” doesn’t necessarily mean better. It doesn’t necessarily mean more just. Our founders understood this. So should we.

We have a republic.

And we should keep it.

I’m Robert George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and Director of the James Madison Program at Princeton University for Prager University.

https://www.prageru.com/video/the-difference-between-a-democracy-and-a-republic